BIN Mentee Spotlight: Zaki Alaoui

Building Scientific Communities That Last: A Guide to Mentorship and Connection

Throughout my early career in neuroscience, I have been fortunate to receive mentorship in experimental techniques, computational modeling, career networking, and the many other skills needed to succeed as a neuroscientist. Importantly, none of this knowledge came from a single individual, it represents the collective contribution of many who chose to invest in me. In this blog post, I want to highlight how both direct and informal mentorship has shaped my growth as a researcher and provide a framework that I believe institutions should adopt when structuring mentorship programs.

I completed my Bachelor of Arts at Amherst College, where I majored in Neuroscience and completed an honors senior thesis with Dr. Michael Cohen. Starting out with zero research experience and taking all of my freshman coursework virtually due to COVID was daunting. I worried about whether I would be able to fit into this high-achieving community, and to be honest, I didn't even know what research looked like in practice. Luckily, one of my chemistry professors, Dr. Christopher Durr, reached out and asked if I wanted to join a summer program called the STEM Incubator Fellowship Program following my freshman year.

The STEM Incubator is designed specifically for students without prior research experience, offering hands-on exploration across chemistry, biology, and data science. What made it transformative wasn't that we were working toward publications or formal research outcomes, it was that I got to try different techniques, make mistakes in a supportive environment, and gradually build confidence in the lab. The Incubator gave me the confidence I needed going into my sophomore year and a much clearer understanding of what research actually entailed. But what made the STEM Incubator truly special wasn't just the summer itself. It was that the faculty remained invested in my success long after the program ended. The directors (Dr. Brittney Bailey, Dr. Marc Edwards, Dr. Christopher Durr) continued to reach out throughout my entire time at Amherst, checking in on how I was progressing in research, academics, and even personally. This kind of sustained mentorship showed me that building a scientific community isn't about a single transformative experience; it's about creating lasting connections where mentors genuinely care about your growth beyond any one project or semester.

Having a community at Amherst College allowed me to feel more comfortable taking scientific risks: enrolling in challenging elective courses, trying new research projects with different professors, and navigating summer fellowship applications. The 'hidden curriculum' of science wasn't outlined to me by any one person, but rather emerged through conversations with students who had gone through similar experiences. Students need both peer mentors who can share lived experiences and navigate the informal rules together, and faculty mentors who can provide formal guidance, open doors to opportunities, and advocate for their growth. Institutions should recognize that neither form of mentorship alone is sufficient. Programs that intentionally cultivate both peer networks and sustained faculty investment, like Amherst's STEM Incubator, create the kind of layered support systems that help students truly thrive in science.

Knowing that I wanted to expand my research experience after Amherst, I joined the Stanford Medicine Post-Baccalaureate Experience In Research. I chose this program not just for the potential to expand my computational and neuroscience research skills, but because the program emphasized community building through a cohort experience. At Stanford, I found mentorship at every stage of the scientific pipeline. My cohort peers became a supportive community, offering valuable feedback and collaboration that made the research journey feel less isolating. Graduate students taught me coding skills and helped me immerse myself in the new field of computational neuroscience, while also sharing honest advice about applying to PhD programs. Postdocs guided me through grant writing and provided feedback on my research proposals. Principal investigators (PIs) offered interview preparation and career guidance that extended far beyond the bench. This multi-layered support system affirmed what I had learned at Amherst: scientific communities thrive when mentorship flows from all directions. Having access to mentors at different career stages meant I could see multiple possible futures for myself in science and receive practical guidance tailored to where I was in my journey.

The communities at Amherst and Stanford were transformative, providing me with the skills, confidence, and networks I needed to pursue neuroscience. Yet I found myself motivated to seek out spaces where I could connect with scientists who looked like me and shared similar experiences navigating academia as underrepresented minorities. This led me to join Black in Neuro! While my previous communities had given me technical skills and mentorship, Black in Neuro offered something equally vital: a sense of belonging and representation. Seeing Black scientists at every career stage, from undergraduates to PIs, expanded my vision of what was possible and reminded me that I belonged in these spaces.

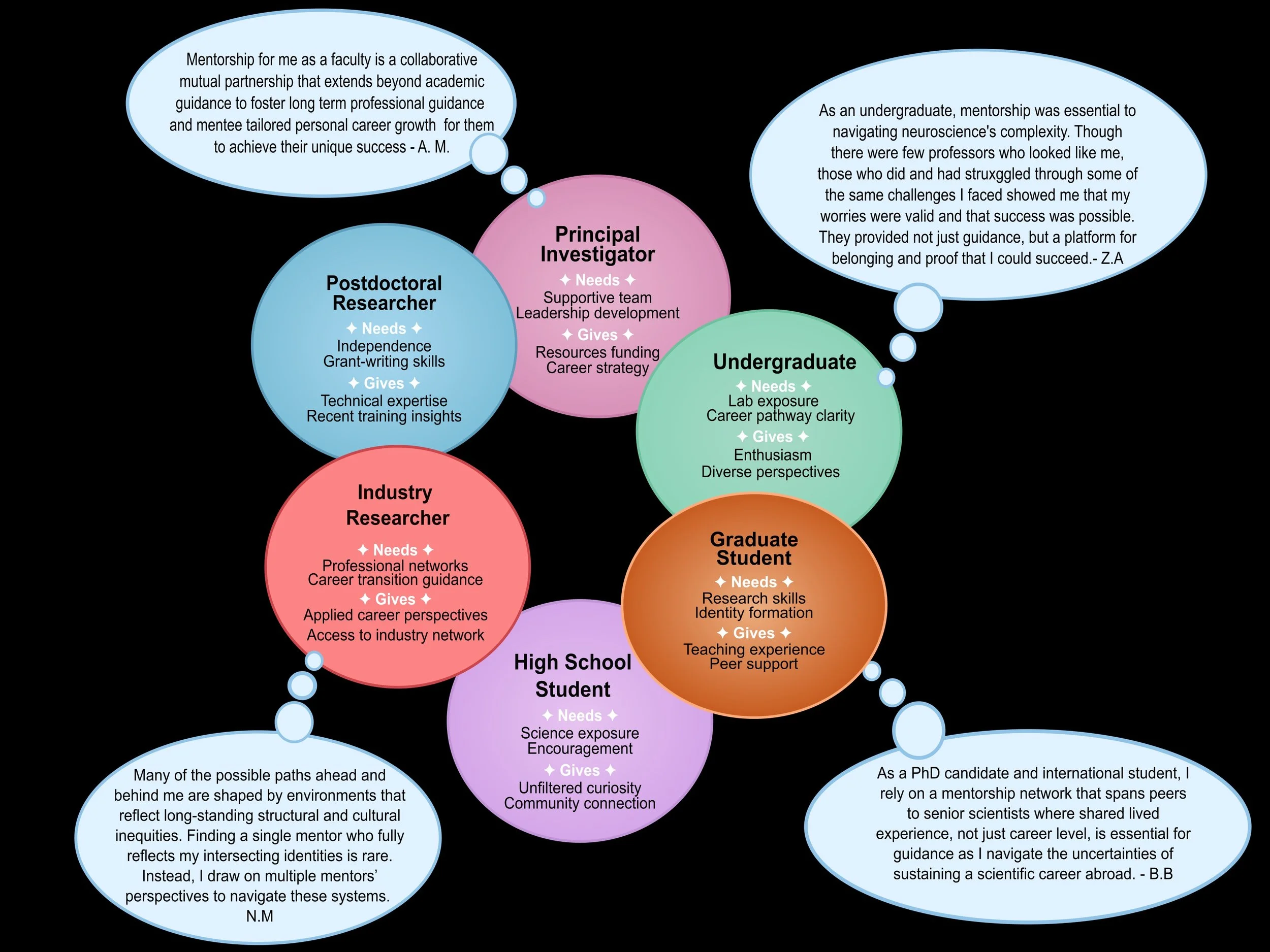

In collaboration with members of the Black In Neuro Mentorship Program, including Betty Bekele, Ngum Agnes Mofor, and Dr. Adejoke Memudu, we developed a framework illustrating how mentorship needs and contributions shift across career stages in science.

Diagram illustrating how mentorship needs and contributions shift across career stages in science.

This diagram emerged from conversations within our community about the support we needed at different points in our journeys. These experiences reveal what a thriving mentorship community needs: intentional structures that connect scientists across career stages, recognition that mentorship must address both technical skills and systemic barriers, and understanding that scientists from marginalized backgrounds often benefit from networks of mentors. Effective communities create spaces where formal programs and peer connections flourish, where representation matters, and where relationships are sustained over time rather than treated as single interactions.

Science is fundamentally collaborative, and the best scientific communities recognize that collaboration extends to include mentorship, support, and knowledge-sharing at all levels. As I continue in my career, I hope to encourage institutions to develop more programs that intentionally build these multi-layered mentorship networks. By investing in sustained relationships across career stages, we can build scientific communities where everyone has the support they need to succeed.

Zaki Alaoui is a Stanford Medicine Postbaccalaureate Research Scholar and recent Neuroscience graduate (magna cum laude) from Amherst College, where he built a foundation in cognitive neuroscience, visual perception, and philosophy of the mind. Currently, his research lies at the intersection of systems neuroscience and artificial intelligence, particularly in understanding how neural circuits in the visual cortex encode sensory information during naturalistic behavior. At Stanford, he is building neural network models of visual cortex activity and developing methods to interpret the internal mechanisms of artificial intelligence. His long-term aim is to establish an independent research laboratory that combines computational modeling with systems neuroscience to understand how the brain transforms sensory input into conscious perceptual experience.