BIN Mentee Spotlight: Samuel Lawal

A Practical Low-Cost Model for In Vivo Electrophysiology

When I first set out to learn how the nervous system talks to itself, I quickly ran into the same practical wall many early career researchers face in Nigeria and similar settings: the tools that let you listen to neurons are expensive, bulky, and often built for labs with deep pockets. Much of biomedical work here focuses on tissue stains, biochemical assays, and behavior, partly because those methods are straightforward and affordable. Yet I am fascinated by systems level questions, by how sensory inputs are integrated and transformed into coordinated motor output and cognition. To study those processes, you need to record electrical activity where it happens, in nerves and cortex, and for that I had to find a different path.

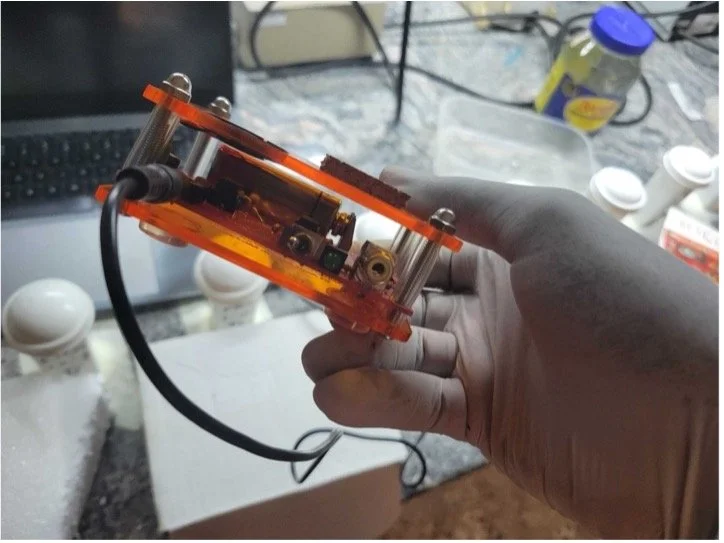

The experiment I designed was deliberately simple, but not simplistic. Working in Dr Oyewole’s lab, I adapted a consumer-oriented amplifier originally intended for insect and surface electromyography, the Backyard Brains SpikerBox, and repurposed it for in vivo recordings from the mouse sciatic nerve and the somatosensory cortex. The goal was to show that a low cost, open-source approach can generate reproducible stimulus response curves with measurable parameters, such as latency, amplitude and conduction velocity. If it could, then foundational electrophysiology would no longer be a gate kept technique but an accessible practice for students and investigators in resource limited environments.

There were technical hurdles. The SpikerBox and similar mobile recorders are not designed for mammalian in vivo work, and the greatest challenge was separating true neural signals from the noise that nonspecialized equipment introduces. To manage this, I combined careful surgical technique and recording discipline with a computational step. I trained a preliminary model on a set of labeled electrophysiological traces to estimate noisiness and flag unreliable segments before analysis. That first pass reduced wasted time at the bench and guided how I filtered and averaged recordings. Building on that, I am now developing a machine learning pipeline that autonomously finds discriminative waveform features, with the aim of making analysis itself accessible and repeatable.

Biology, though, remained the central question. I used the protocol to explore whether common monosaccharides modulate neural excitability at the level of peripheral nerve and cortex. We know that sugars are the brain’s primary fuel, and that glucose, fructose and galactose enter and are metabolized by cells through different pathways, but their acute effects on neural excitability are not well described in vivo. Using a combination of acute topical application and a short chronic administration scheme, I recorded compound muscle action potentials from the gastrocnemius, sciatic nerve responses, and cortical potentials evoked by paw stimulation. The recordings produced measurable changes across conditions, and importantly, they were reproducible using the low-cost setup. Analysis so far suggests differential modulatory effects depending on the monosaccharide and the time course of administration. I am continuing statistical validation, and the work is currently submitted as an abstract for Surgery Research Day 2025 at the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital.

If there is a lesson from doing electrophysiology on a shoestring budget, it is that constraint breeds clarity. Working without expensive black box recorders forced me to think carefully about what signals I truly needed, and what steps in preparation, stimulation and averaging made those signals robust. It also forced an ethic of transparency. A low-cost protocol only helps if it is documented, reproducible and paired with open analysis tools available to low-resource scientists like myself. That is why the method I describe focuses on simple consumables, clear electrode placement landmarks, and a stepwise recording and signal quality workflow that others can follow and adapt.

There is a broader implication here that goes beyond a single protocol. Science should not be geographically gated. When students can learn to record and reason about neural activity with affordable tools, we democratize not just training but the kinds of questions that get asked. Labs in cities and regions overlooked by major funding streams have unique access to different populations, ecological contexts and experimental creativity. Affordable science amplifies those strengths rather than asking investigators to conform to a narrow set of resource expectations.

Finally, this project is personal. It is the product of slowly building confidence in a field that can at times feel exclusionary. It is also practical optimism. If a consumer amplifier, careful technique and a bit of machine learning can demonstrate reproducible modulation of neural excitability in vivo, then we have one more instrument for teaching, for early discovery, and for broadening participation in neuroscience. I hope this protocol becomes a starting point, not an endpoint: a way for students and early career researchers to ask bolder questions about how neural circuits function and change, without waiting for the improbable gift of top tier equipment.

About the author

Samuel Lawal is a recent Human Physiology (First-Class Honours) from the University of Ilorin, where he built a strong foundation in neuroscience, systems regulation, and experimental design. His research experience lies at the intersection of cognitive neuroscience and computation, particularly in understanding how neural activity patterns underlie perception and behavior. During his undergraduate studies, he worked on projects involving EEG-based analyses of neural oscillations and designed simplified frameworks for studying neural responses in low-resource settings. He is also exploring the use of machine learning models to improve neural signal interpretation and reduce human bias in electrophysiological data analysis. His broader goal is to contribute to systems-level neuroscience by developing computational and experimental tools that advance our understanding of brain function and its translation into real-world applications.

Contact- LinkedIn